Coffeenomics, social responsibility, and CAN coffee (a review)

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 3:15PM

Wednesday, December 14, 2011 at 3:15PM Classical economic theory proposes that the sole purpose of a business is to enrich the shareholders of a company. The profits it generates will eventually circulate into the wider economy and improve the material well-being of everyone in the society (the idea that a “rising tide lifts all boats”). The conclusion of this is that focusing on anything other than profits would hurt the value of the company and therefore society.

The theory is controversial, to say the least. In the short term, its implementation ignores many externalities (pollution, labor market instability, etc.) that are detrimental to society as a whole. Another weakness of the theory is that it relies on the belief that money (and what it buys) is the equivalent of satisfaction (utility). Notwithstanding, it is an idea that many people subscribe themselves to. They believe that profits are the only important thing in business, and any discussion of business’ effects on the environment or the rest of society are dismissed as leftist conspiracies to bring down capitalism.

While there are some leftists who do want to get rid of capitalism, there is a wide middle ground between the two viewpoints. More today than ever before, select business leaders realize that taking care of the environment and the people who work for them are important too. In Portland, for example, many coffee companies have taken up the mentality that they want to treat their employees and coffee growers fairly. Portland Roasting is a leader in this area, but is not the only one building stronger links between the coffee growers and coffee drinkers. If you stop in at Stumptown’s Annex, for example, you can learn about several of the growers who raise coffee for the company. By raising the profile of the growers, roasters can differentiate the coffees more easily and sell them at higher prices.

Whereas Portland is the leader in producing more sustainable coffee, the city’s coffee companies do not hold a monopoly on trying to make the world a better place. Smaller roasters in Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, Kansas City, Durham and other cities across the country are building a movement that is benefiting coffee drinkers and coffee farmers.

CAN Coffee

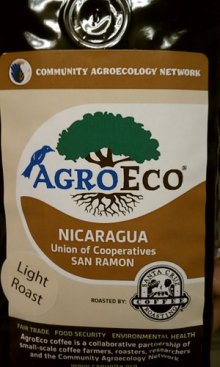

One participant in this movement is an organization known as the Community Agroecology Network (CAN), based in Santa Cruz, California. In 2001, CAN was founded by Dr. Stephen Gliessman, a researcher in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz, and Robbie Jaffie, also a lecturer in environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz. CAN comprises a network of coffee cooperatives that includes communities in four coffee-producing countries—Mexico, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Nicaragua—as well as resources from UC Santa Cruz. The coffee is grown and processed outside the US by the cooperatives then sent to the United States. Santa Cruz Coffee Roasting Company roasts the coffee once it arrives and CAN sells it under the AgroEco label.

CAN recently sent me a bag of AgroEco coffee for review [note: CAN sent the coffee at no charge, but none of the links are affiliate links]. The coffee arrived at my house in a vacuum-packed bag. It was labeled as a single-origin, light roast from a coffee cooperative in Nicaragua called Union de Cooperativas Augusto Cesar Sandino (also called UCA San Ramón, or UCASR). I looked for a roast date on the package, but could not find one. When I asked Daniel Fuentes, CAN’s Marketing Coordinator, about this, he told me the company roasts in small batches and goes through its inventory in less than two weeks, so when the coffee arrives in the customer’s mailbox, it will have been between one and three weeks since being roasted. CAN will grind the coffee if a customer chooses (but if you care about freshness, why would you do that?).

Fresh out of the French press, the coffee had a sweet aroma, but the sweetness did not dominate the coffee. I picked up hints of unsweetened baker’s cocoa and rose petals in the medium-bodied brew.

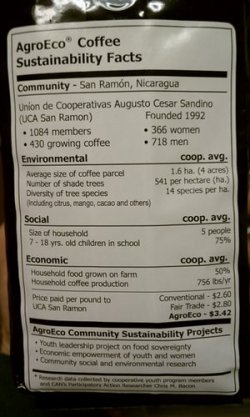

The thing that stood out the most to me about CAN’s coffee was its unique label. Most coffee labels trumpet the coffee’s unique flavors, or highlight its story, but the AgroEco label was primarily used to give the facts about the coffee’s sustainability. If you look at it in the picture, you can see what makes the label unique. CAN is very transparent about where the coffee came from, the demographics of the coffee farmers in the cooperative, and the prices that farmers received for the coffee. The cooperative received $3.42/lb for the coffee, significantly higher than the Fair Trade price or the market price for coffee.

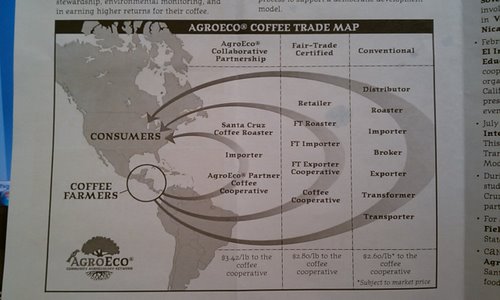

How can the farmers be paid a higher price for the coffee and the roaster still make money? One of the ways CAN does this is by cutting out middlemen between the growers and the roaster. Coffee typically passes through several hands before it reaches the consumer, each of which take a cut of the purchase price. In this case, the coffee goes from the coffee cooperative through an importer directly to the roaster, who then sells the roasted coffee to consumers. The more direct supply chain lowers overhead costs, making the coffee more profitable for both producer and roaster.

Though not certified as organic, the coffee from UCASR is grown without pesticides or herbicides. The costs involved with obtaining certification can be too high for some farmers, and the return on the investment does not always pay off. One of CAN’s goals is to help promote farmers who produce their coffee without chemicals, whether or not they obtain the official organic certification.

The coffee from UCA San Ramón is also shade-grown, so instead of clear-cutting forests to grow only coffee, the coffee is grown beneath other trees. Mango, citrus and cacao trees are grown in and around the coffee, providing additional food and income for cooperative members. Thus, the shade-grown coffee helps diversify the farmers’ production risk and increases their food security. Raising coffee this way also provides more habitat for wildlife, especially migratory birds.

CAN shortens the supply chain to provide more benefits to growers

CAN shortens the supply chain to provide more benefits to growers

Overall, the quality of the AgroEco coffee was somewhere between Ristretto (perhaps Portland’s best) and Starbucks coffee. If social and environmental issues factor heavily in your coffee-purchasing decisions, AgroEco coffee would be worth checking out. Given the company’s transparency, you can feel confident you are supporting coffee growers and their communities. In a country where the collective spending decisions of consumers shape the direction of both economic and political decisions, choosing which products to carries much responsibility. The choices are yours, make them wisely.

For more information about CAN, visit http://www.canunite.org.