[Part 1 of this story can be found here]

Nossa Familia (“Our Family”) Coffee was founded by Augusto Carvalho Dias Carneiro. Augusto grew up in the city of Rio de Janeiro, but the family’s farm was never very far from his mind. Dias would spend 3-4 months each year there, riding the horses that his grandfather used to herd cattle. The time in the country made a deep impression on him, and each year he looked forward to returning.

Fate brought Augusto to Portland from Brazil. He knew he wanted to study engineering and play tennis at an American college, but did not have a strong preference for a particular place.

“It was the luck of the draw. I sent letters to over 120 schools. I wanted to play tennis and go to school, and I just ended up here.”

The University of Portland responded, and Augusto decided to come to Portland, sight unseen. Before he came, he envisioned himself needing to learn about American sports like baseball and football. When he arrived on campus in the fall of 1996, the university’s soccer-crazy culture made him feel right at home (if you haven’t heard, soccer is fairly popular in Brazil too). The Portland area’s numerous opportunities for biking and the city’s love of coffee also made Portland a good fit for him.

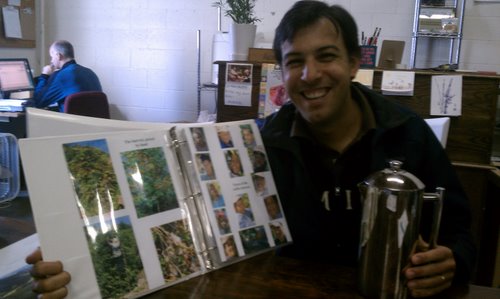

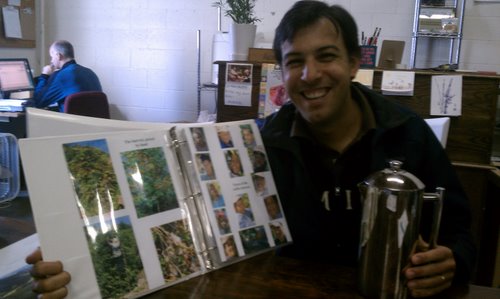

Augusto Carvalho Dias Carneiro, with a notebook containing pictures of the family's coffee farm in Brazil

Augusto Carvalho Dias Carneiro, with a notebook containing pictures of the family's coffee farm in Brazil

After graduation, Augusto got a job as an engineer, but quickly found that engineering was not what he wanted to do. He missed Brazil, and was looking for a reason to travel there more frequently. Starting a coffee company was one way to make that happen. Visiting the country in 2004, he spoke with one of his cousins, telling him he was considering importing coffee from the family’s farms to Portland.

The cousin thought it was a good idea, so he sent Augusto back to Portland with 70 pounds of coffee roasted on the farm in Brazil. Augusto brought the coffee back and shared it with family and friends. It was a hit, and Augusto, along with one of his friends from college (no longer invested in the business) decided to start a company.

Each partner put in $400 to bring the first shipment up via FedEx. The coffee sold well. In those days, coffee was much cheaper and the Brazilian real was much weaker than the US dollar, so shipping the coffee up in small quantities was profitable. Still, they knew that bringing the coffee to Portland this way was not going to be the long-term business model, and began looking for other ways to supply Brazilian coffee to the Portland market.

As the company’s wholesale customers began to ask for different types of packaging, various lead times and freshness levels, importing the coffee eventually became too difficult, so they had to come up with another way to bring the coffee to Portland.

Augusto decided the best way to do that would be to partner with a local roaster. He found one in Kobos Coffee. Augusto had met David Kobos and Brian Dibble, Kobos’ owners, when he stopped in to see if they might be interested in buying some green Brazilian beans. Eventually, they came to an agreement where Nossa Familia would import the green beans and Kobos would roast them.

“Partnering with Kobos has been good for us. We can combine my family’s coffee knowledge with their roasting knowledge,” Augusto said.

Nossa Familia employees unload and store the green coffee in Kobos’ warehouse, and Kobos’ roasters roast the coffee twice per week, using specifications that the family’s coffee experts in Brazil supply.

Currently, much of Nossa Familia’s coffee is sold through supermarkets, especially New Seasons. The company’s coffee is also available at some local cafés and restaurants. In the future, Nossa Familia plants to start roasting its own coffee and have its own branded café. Augusto said that when they open the roastery/cafe, it will be easier to share seasonal coffees and micro-lots with their customers. The company may also bring in coffee from other farms in Brazil or other countries that share the same values, creating an “extended familia”.

Farm, family and fun – The adventure of a lifetime

For someone who wants to see firsthand how coffee is grown and processed, Nossa Familia has started the tradition of taking groups of people to Brazil on its annual Coffee Tour. The next trip, which is the fourth one, will take place May 4-14, 2012. The date coincides with the beginning of coffee harvest.

The origins of the trip share a connection with Augusto’s passion for cycling. He is an avid biker, and Nossa Familia has sponsored Cycle Oregon for several years. For a long time, the ride’s director kept asking Augusto when they were going to Brazil, until one day they finally decided to go ahead and plan the trip. The first one, in 2008, was just a group of friends biking around the countryside. Most of the people brought their tents and camped out at night under the stars. The weather cooperated—most of the time.

“One day a huge storm came in, and we were in the house and you could see the tents being folded flat by the wind. Everything got soaked.” Augusto recalled.

Unplanned weather events notwithstanding, the trip was a success, so they decided to do it again the next year. The first tours were focused on biking, with lots of planned activities. The group covered many miles on their bikes as they rode around the rolling hills of the countryside. The second and third trips were different. The group spent less time biking and more time doing other things.

“You can go biking everywhere,” Augusto explained, “so the goal became just to experience the culture and everything there is to see.”

It is not only rural Brazil that the travelers get to experience. Fazenda Cachoeira is located about eight miles outside Poços de Caldas, a town of about 200,000 people, so in addition to experiencing life in the country, you also get a glimpse of life in the city.

“We do the cultural thing as well. There is a lively arts and crafts market in the city, and you can visit several restaurants. You’re not just sitting around the middle of nowhere.”

Augusto leads the trip himself. One of the highlights is to observe and participate in the coffee operation. Travelers can help pick the coffee cherries from the trees and then watch as they are processed into green beans, ready to be exported throughout the world.

Sarah, who went on the 2011 trip, recalled picking some unique coffees: “We were able to harvest coffee from these hundred-year-old coffee trees [Fazenda Santa Alina has a “centennial grove,” where none of the plants have been taken out since they were planted in 1907], and you could take a cherry off the plant, toss it in your mouth. When you bit into it, it tasted like honey—super sweet, but it doesn’t have the depth of fruit that a typical cherry would.”

For people nervous about traveling to a country where English is not the main language, Augusto said that a majority of the middle-class Brazilians have taken some English, so they at least know the basics. At the farm, though, very few people speak English, which can lead to some entertaining cultural exchanges. He recounted returning to the farm one evening to find a group of Americans and Brazilians sitting around trying to teach each other their language.

“Someone would pick up an object and say the name in English, then someone from the Brazilian group would try to repeat the word. Everyone would get a good laugh when the person mispronounced the word. They were doing the same for Portuguese.”

Cultural exchanges like this one are an integral and invaluable part of the trip.

Lasting impressions

When I asked what he thinks is the best part of the trip, Augusto responded that it is “not so much the coffee, but the family. It’s something you can’t sell.”

For example, Augusto’s grandparents still live on the farm and one evening, they invite the trip’s guests into their house for dinner. It is an opportunity to share stories, culture and great Brazilian food.

Sarah, who went on the most recent trip, also shared what impressed her the most.

“For me, what I came back with—not having been in the coffee industry for a long time—was that I had no concept of what it took to get a green bean to the United States. It did not occur to me the effort, the level of care, all of the processes it took to get there. We were talking about the beans being dried to the correct humidity, but the coffee also has to sit and rest for 60-90 days before it can be shipped. There’s the storage and all the equipment and above all, the people. The best part was meeting Tuca [one of Augusto’s cousins, and manager of one of the farms] who said ‘I’m not a grower of coffee, I’m a leader of people.’ I really forget that’s what it’s about. You can have a product at the end of the day, but if you don’t take care of the people, it’s not worth it. That made a huge impact.”

Coffee has a way of bringing people together, and Nossa Familia was founded on the idea that coffee could provide a bridge between Portland and Brazil. In Nossa Familia’s case, the coffee brings cultures and family together. After speaking with Augusto and Sarah, it was clear that above all, family is the focus of Nossa Familia. One of the sayings at Nossa Familia is that instead of “fair trade,” the company engages in “family trade.” For generations, the Carvalho Dias family’s coffee heritage has been cultivated by people who care about sustainability and high-quality coffee. In these values, Portlandians and Brazilians have something in common.

Finally, the giveaway!

This year, for the first time ever, Nossa Familia is giving away a free trip for two to Brazil!

Taking the trip to the farm would be a valuable opportunity to learn about coffee production and to soak up the culture of Brazil. The eleven-day trip is full of activities, and a complete itinerary can be found at Nossa Familia’s website. If you don’t happen to win, you can still go. The full cost of the trip is $2950 per person, plus airfare, so start saving up.

No purchase is necessary to be eligible for the sweepstakes. The easiest way to enter the contest is to go to Nossa Familia’s contest page on Facebook. If you do not have a Facebook account, you can still enter. Click on the link to the contest and then click on "Read the Official Rules." Towards the bottom of that page there is a link to an "Alternative Method of Entry." Click on that link and enter your information. People aged 18 to 99 who reside in the US are eligible to enter. Don’t delay—the sweepstakes ends November 1, 2011, at 4:59am—you don’t want to miss this opportunity.

Good luck! (and if you win, feel free to take me!)

[Special thanks to Kevin, who worked hard to make sure my shot of espresso was pulled just right. It was tasty.]

Sunday, June 30, 2013 at 8:33PM

Sunday, June 30, 2013 at 8:33PM

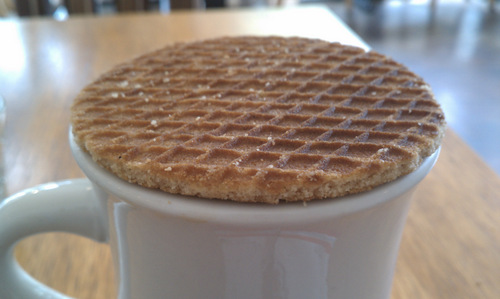

Rip van Yum

Rip van Yum Tough to resist

Tough to resist